Business inventories econ invites you to explore the fascinating world of how companies manage, measure, and respond to inventory changes in economic landscapes. Whether you’re a business owner, student, or curious observer, understanding the movement and management of inventories sheds light on the inner workings of economies and the strategies behind successful organizations.

At its core, business inventories econ covers everything from the basic definitions and importance of inventories in economics to the methods companies use to track and value their stock, such as FIFO, LIFO, and weighted averages. You’ll discover how inventory levels influence economic growth, how technology is revolutionizing inventory tracking, and the unique practices across industries like manufacturing, retail, and e-commerce. This comprehensive overview provides a window into how inventories serve as both an indicator and driver of broader economic trends.

Definition and Importance of Business Inventories in Economics

Business inventories represent the total stock of goods held by firms at any given point in time. Within the context of economic activity, these inventories include everything from raw materials awaiting production to finished goods ready for sale. Understanding business inventories is essential because they serve as a crucial link between production and sales, directly affecting cash flow, operational efficiency, and broader economic indicators such as GDP.

Tracking inventories is vital for both businesses and policymakers. For businesses, efficient inventory management enables better demand forecasting, reduces storage costs, and helps prevent stockouts or overstocking. On a macroeconomic scale, fluctuations in inventories can signal shifts in demand or production trends, making inventory data a key component for analyzing business cycles and economic health.

Main Types of Business Inventories

Business inventories can be classified into several main categories, each representing a distinct stage in the production and sales process. Understanding these types helps companies tailor their inventory strategies and provides economists with a clearer picture of supply chain activity.

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Materials | Basic inputs yet to be processed or used in manufacturing. | Steel for car manufacturing, cotton for textile production |

| Work-in-Progress (WIP) | Goods that are partially completed during the manufacturing process. | Unfinished furniture, partially assembled electronics |

| Finished Goods | Products that are completely manufactured and ready for sale. | Packaged food items, fully assembled smartphones |

| Maintenance, Repair, and Operating (MRO) Supplies | Items used to support production processes, not part of the final product. | Lubricants, cleaning agents, spare machine parts |

Why Tracking Inventories Is Critical

Monitoring inventory levels helps businesses maintain the delicate balance between meeting customer demand and minimizing holding costs. On a broader scale, economists use inventory data to gauge the health of industries, predict future output, and assess the stability of supply chains. When inventories rise faster than sales, it may suggest slowing demand or overproduction, signaling caution for future business decisions and economic forecasts.

Methods for Measuring Business Inventories

Accurately measuring and valuing business inventories is fundamental to both internal decision-making and compliance with accounting standards. Different methodologies can lead to varying inventory valuations, impacting reported profits, taxes, and financial ratios.

Common Inventory Valuation Methods

There are several widely adopted methods for inventory measurement, each with its own effect on financial statements and operational analysis.

| Method Name | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-In, First-Out (FIFO) | Assumes the first items purchased are the first sold; ending inventory reflects latest costs. | Aligns with actual flow for many products; higher profits during inflation; balance sheet reflects current values. | May increase tax liability in times of rising prices; less matching of current costs with revenues. |

| Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) | Assumes the last items purchased are the first sold; ending inventory reflects older costs. | Lower tax liability during inflation; matches recent costs with revenues. | Banned under IFRS; inventory values may be outdated on balance sheet; not always realistic in physical flow. |

| Weighted Average Cost | Calculates average cost of all inventory items available for sale during the period. | Smooths out price fluctuations; simple application; fair for homogenous items. | May not reflect actual physical flow or most recent costs; can distort profit margins in volatile markets. |

Reporting Inventory Levels in Economic Statistics

National economic data on inventories provides insights into trends and future directions of the economy. The reporting procedure typically involves the following steps:

- Businesses conduct regular physical counts and reconcile records to determine current inventory levels.

- Inventory data is aggregated across sectors and submitted to national statistical agencies, such as the U.S. Census Bureau.

- Agencies analyze and adjust the data for seasonal and cyclical variations.

- Reports are published monthly or quarterly, often included in broader economic releases like GDP and manufacturing surveys.

- Economists and policymakers interpret these figures to assess production trends, supply chain robustness, and economic momentum.

Economic Impact of Inventory Changes

Shifts in business inventories can have significant repercussions on the overall economy. Changes in inventory levels not only affect a company’s operational performance but also serve as a key component in the calculation of GDP, making them integral to understanding economic cycles and forecasting trends.

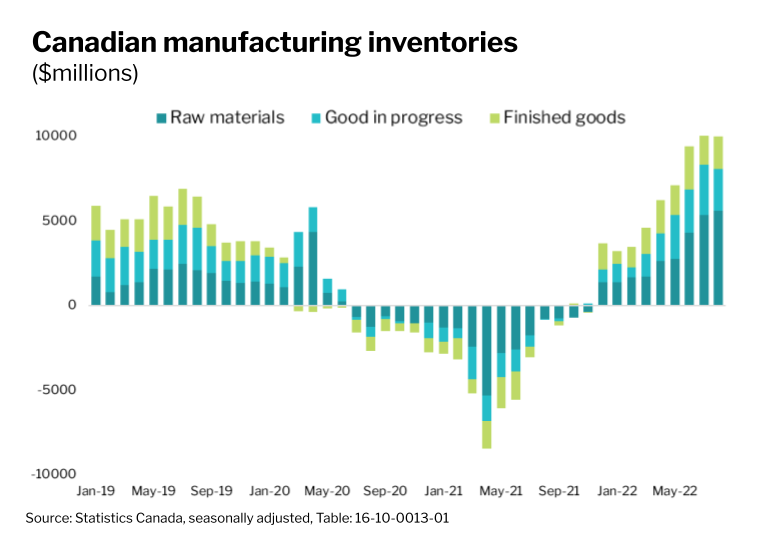

Effects of Inventory Fluctuations on GDP and Business Cycles

Inventory buildup or depletion can either boost or drag down economic growth rates. When businesses accumulate inventories, it often signals optimism about future demand, contributing positively to GDP. Conversely, inventory drawdowns may indicate either strong sales outpacing production or anticipation of weaker demand, with mixed implications for economic growth.

Illustrative Scenarios of Inventory Buildup and Depletion

To better understand the connection between inventory movements and business performance, consider the following examples:

- During periods of rising demand, a retailer boosts inventory in anticipation of busy seasons, supporting higher sales and GDP growth.

- In a manufacturing slowdown, firms allow inventories to decline, signaling a potential contraction in economic activity and reduced production schedules.

- If supply chain disruptions occur, companies may build up buffer stocks, leading to short-term increases in inventory but potential inefficiencies if demand does not materialize.

Consequences of Inventory Mismanagement

Managing inventories inefficiently can create ripple effects throughout the supply chain and impact pricing strategies. Key consequences include:

- Increased storage and handling costs due to overstocking.

- Stockouts leading to lost sales, dissatisfied customers, and damaged brand reputation.

- Obsolete inventory resulting in write-offs and reduced profitability.

- Price volatility stemming from abrupt changes in supply-demand dynamics.

- Disrupted production schedules that affect supplier and customer relationships.

Inventory Management Techniques in Business Operations

Effective inventory management strategies are essential for maintaining operational efficiency, meeting customer expectations, and optimizing working capital. Companies across industries leverage a variety of techniques tailored to their unique production cycles, demand variability, and market conditions.

Key Inventory Management Strategies

Selecting the right inventory management method can greatly improve a company’s responsiveness and cost structure. The following table summarizes common strategies, their characteristics, and their practical considerations.

| Technique | Key Features | Ideal Use Case | Potential Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Just-In-Time (JIT) | Minimizes inventory by aligning deliveries closely with production schedules. | Environments with predictable demand and reliable suppliers, such as automotive manufacturing. | Highly sensitive to supply disruptions; requires robust supplier relationships and real-time data. |

| Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) | Calculates optimal order size to minimize total ordering and holding costs. | Stable demand and consistent ordering patterns, often in manufacturing or distribution businesses. | Less effective with fluctuating demand; requires accurate cost and demand estimates. |

| Safety Stock | Maintains extra inventory to buffer against demand surges or supply delays. | Industries with unpredictable demand or long lead times, such as electronics retail. | Can increase carrying costs and risk of obsolescence if not carefully managed. |

Implementing Inventory Control Systems

Modern businesses rely on a structured approach to inventory management, often supported by technology. The typical procedure includes:

- Assessing current inventory processes and identifying pain points.

- Choosing appropriate inventory management techniques and software solutions.

- Training staff on new systems and establishing protocols for regular audits.

- Integrating inventory data with other business functions, such as procurement and sales, for greater visibility.

- Continuously monitoring performance metrics and making adjustments as market conditions evolve.

Business Inventories and Economic Indicators: Business Inventories Econ

Business inventory data serves as a valuable barometer for economic health, offering insights into supply chain activity, production planning, and future demand. As such, inventory levels are closely monitored by economists and policymakers to inform decision-making and economic forecasts.

Role of Business Inventories as Economic Indicators, Business inventories econ

Inventories can function as both leading and lagging indicators, depending on economic context. A rise in inventories might signal anticipated growth or, alternatively, a mismatch between supply and demand. Conversely, falling inventories could indicate strong sales or reduced production activity.

“Economists and policymakers interpret rising business inventory levels as potential signs of either growing confidence in future demand or accumulating unsold goods, while declining inventories may reflect robust sales or cautious optimism about future growth.”

Major Government Reports and Datasets for Business Inventories

National statistics offices regularly publish inventory data, which forms part of key economic indicators. Some of the most widely referenced reports include:

- Manufacturing and Trade Inventories and Sales (MTIS) report by the U.S. Census Bureau

- Monthly Wholesale Trade Survey

- Retail Trade Inventories report

- Quarterly Financial Reports for Manufacturing, Mining, and Trade Corporations

- GDP and National Accounts publications, which integrate inventory changes into broader economic measures

Technological Innovations in Inventory Tracking

Technological advancements have transformed inventory tracking, making processes more accurate, efficient, and responsive to real-time changes. Businesses across industries are leveraging digital tools to optimize their inventory management and reduce the risks of errors and miscounts.

Modern Inventory Tracking Technologies

The adoption of advanced technologies has introduced new possibilities in tracking, tracing, and managing inventories at scale. The following table highlights some of the most impactful innovations.

| Technology | Functionality | Benefits for Businesses | Adoption Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFID (Radio-Frequency Identification) | Uses radio waves to automatically identify and track tags attached to products. | Enables real-time visibility, reduces manual labor, improves accuracy. | Requires upfront investment; integration with legacy systems can be challenging. |

| Barcoding | Encodes product information in visual codes for automated scanning and tracking. | Cost-effective, widely adopted, increases speed and reduces errors in inventory counts. | Relies on line-of-sight scanning; less effective for large-scale automation without supporting systems. |

| Inventory Management Software | Digital platforms for tracking, analyzing, and optimizing inventory workflows. | Centralizes data, enables demand forecasting, integrates with other business systems. | Implementation complexity; requires user training and ongoing maintenance. |

Automation and Real-Time Inventory Control

Automation allows companies to maintain accurate inventory records without the need for constant manual oversight. For example, a warehouse equipped with RFID readers and sensors can automatically update inventory counts as items move in or out, flagging discrepancies instantly. Real-time tracking enables businesses to respond swiftly to demand changes, restock efficiently, and reduce the risk of errors that could disrupt operations. These innovations help companies maintain optimal inventory levels, enhance customer service, and improve supply chain resilience.

Sector-Specific Inventory Practices and Trends

Inventory management is not a one-size-fits-all practice; each industry faces unique challenges and adopts tailored strategies to optimize stock levels, turnover, and operational costs. Understanding these differences is crucial for benchmarking performance and identifying best practices.

Inventory Management in Key Sectors

The approach to inventory management varies significantly between manufacturing, retail, and wholesale sectors. The table below compares typical inventory turnover ratios, reflecting how efficiently companies convert stock into sales.

| Sector | Typical Inventory Practices | Inventory Turnover Ratio (Annual Average) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | Balances raw materials, WIP, and finished goods; often uses JIT and EOQ. | 6–12 | Depends on production cycle length and product complexity. |

| Retail | Focuses on finished goods; rapid turnover, frequent restocking, seasonal adjustments. | 8–15 | Turnover higher in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG). |

| Wholesale | Handles bulk purchases and distribution; emphasizes logistics and order fulfillment efficiency. | 5–10 | Inventory levels fluctuate with demand from retailers. |

Recent Trends and Challenges in Business Inventories

E-commerce growth and global supply chain disruptions have reshaped inventory management priorities. Key trends and challenges include:

- Increased adoption of real-time inventory tracking to meet omnichannel demands.

- Greater emphasis on supply chain resilience, with businesses diversifying sourcing strategies.

- Pressure to minimize inventory holding costs while maintaining high service levels for online shoppers.

- Shorter product life cycles and the need for agile inventory adjustment in response to market changes.

- Integration of sustainability goals, such as reducing waste and optimizing returns management.

Last Recap

In summary, business inventories econ is much more than just numbers on a balance sheet—it’s a dynamic field shaping both daily business operations and national economic policies. By mastering the nuances of inventory management, businesses can boost efficiency, navigate market shifts, and contribute valuable insights into economic forecasts. Staying informed about evolving inventory practices ensures that organizations remain agile and competitive in a rapidly changing world.

FAQ Resource

How do business inventories affect a company’s cash flow?

Business inventories tie up cash because they represent products that have been purchased or produced but not yet sold, impacting the company’s liquidity and cash flow management.

What happens if a business holds too much inventory?

Holding excessive inventory can increase storage costs, risk of obsolescence, and reduce cash availability for other investments.

Why do economists track inventory levels?

Economists monitor inventory levels to understand business cycles, predict economic growth, and assess supply chain health, as changes in inventory often signal shifts in demand or production.

Can inventory data help predict recessions?

Yes, significant inventory buildups can indicate decreased consumer demand, potentially signaling an upcoming economic slowdown or recession.

Are inventory management practices different for online businesses?

Yes, e-commerce businesses often require faster, more flexible inventory systems to manage rapid order fulfillment and frequent changes in consumer demand.